Colloquium

Carbon in disks and rocky planets

Dr. Carsten Dominik

(Anton Pannekoek Institute of Astronomy, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands)

Dienstag/Tuesday, 2019-04-23 14:00 c.t., Raum 114

Eugene-Paul-Wigner Gebäude, Hardenbergstr. 36, 10623 Berlin

Zusammenfassung/Abstract:

While carbon is one of the five most abundant elements in the universe, the Earth is surprisingly poor in carbon. With respect to silicon, its abundance is down by about a factor of 10000. This fact could be considered as surprising because meteorites contain carbon in the form of diamonds, graphite and also organic material with sublimation temperatures above those expected in the solar nebula the location where the Earth formed. A number of special processes have been suggested to move the solid carbon into the gas phase of a planet-forming disk before solids are gathered to form planets. I will show that the currently favoured explanation does not work and that it is therefore conceivable that rocky planets with appreciable carbon abundances do exist. I will discuss the properties of such planets using the results of geophysical models and high temperature/pressure experiments.

Simulations of the Fast and Furious Lives of High Velocity Clouds

Prof. Dr. Robin Shelton

(Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Georgia)

Donnerstag/Thursday, 2017-05-11 17:15, EW 202

Eugene-Paul-Wigner Gebäude, Hardenbergstr. 36, 10623 Berlin

Zusammenfassung/Abstract:

Sensitive observations have found enormous clouds of material beyond our Milky Way Galaxy. Some are as large as mini-galaxies with as much mass as 100 million Suns. Others are shreds that were ripped from nearby galaxies. Additional observations show that several nearby clouds are currently interacting with our own Galaxy. Some have reportedly shot through the Milky Way’s disk while others are currently passing through the less dense outskirts of our Galaxy. My group has been computationally modeling these clouds, called high velocity clouds (HVCs), in order to determine how they affect our Galaxy and how our Galaxy affects them. In this presentation, I will show how HVCs behave on timescales of hundreds of millions of years, how they shed streamers of highly ionized gas that become incorporated into our Galaxy, and what happens when they collide with the dense gas in our Galaxy’s disk.

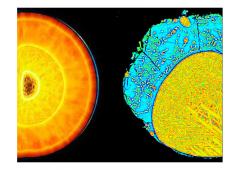

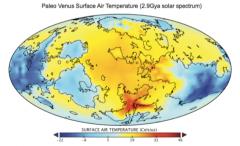

Was Venus the first habitable world of our solar system?

- Paleo Venus Surface Air Temperature (2.9 Gya solar spectrum)

- © Way et al., Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 8376 (2016)

Dr. Michael Way

(NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, New York)

Freitag/Friday, 2017-03-24 14:00 c.t., EW 114

Eugene-Paul-Wigner Gebäude, Hardenbergstr. 36, 10623 Berlin

Zusammenfassung/Abstract:

A great deal of effort in the search for life off-Earth in the past 20+ years has focused on Mars via a plethora of space and ground based missions. While there is good evidence that surface liquid water existed on Mars in substantial quantities, it is not clear how long such water existed. Most studies point to this water existing billions of years ago.

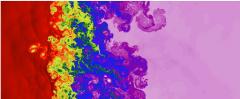

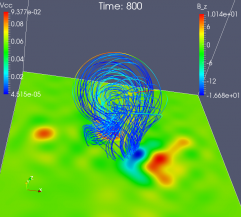

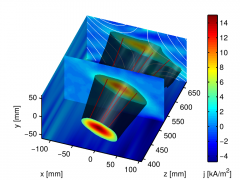

Multiple-scale current sheet dynamics of guide-field reconnection

- 3D current sheet (with sample magnetic field lines).

- © von Stechow, Grulke, Klinger, Plasma Phys. Contr. F., 58, 014016 (2015)

Dr. Adrian von Stechow

(Institut für Plasmaphysik; Greifswald)

Freitag/Friday, 2016-12-16 14:00 c.t., EW 561

Eugene-Paul-Wigner Gebäude, Hardenbergstr. 36, 10623 Berlin

Zusammenfassung/Abstract:

Magnetic reconnection is a generic plasma process that enables the release of accumulated magnetic energy by rapid changes in magnetic topology, generating fast particles and allowing a wealth of instabilities to grow. A central feature is the formation of a highly localized current sheet. Its detailed properties determine the rate at which reconnection proceeds and must be considered on many different spatial and temporal scales. These range from the global boundary conditions, to its plasma parameters all the way down to microscopic fluctuations stemming from instabilities.

MHD Turbulence and the Geodynamo

John V. Shebalin

(NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas, USA, and George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia, USA)

Freitag/Friday, 2016-11-25 14:00 c.t., Raum EW 431

Eugene-Paul-Wigner Gebäude, Hardenbergstr. 36, 10623 Berlin

Zusammenfassung/Abstract:

Recent research results concerning forced, dissipative, rotating magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) turbulence will be discussed. These results come from very long-time Fourier method (periodic box) simulations in which forcing contains varying amounts of magnetic and kinetic helicity will be presented. They indicate that if dissipative MHD turbulence is forced so as to produce a state of relatively constant energy, then the largest-scale components are dominant and quasi-stationary, and produce an effective dipole moment vector that aligns closely with the rotation axis.

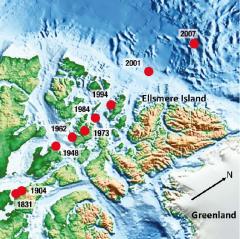

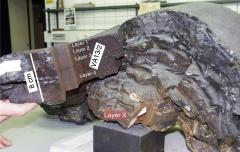

⁶⁰Fe and ²⁴⁴Pu in deep-sea archives — a link to nearby supernova activity and r-process sites

Dr. Anton Wallner

(Australian National University, ACT, Australia)

Freitag/Friday, 2016-10-21 14 c.t., EW 561

Eugene-Paul-Wigner Gebäude, Hardenbergstr. 36, 10623 Berlin

Zusammenfassung/Abstract:

The Interstellar Medium (ISM) is continuously fed with new nucleosynthetic products. Presence of radionuclides live in the ISM is evidenced by space-born γ-ray telescopes. The solar system moves through the ISM and collects dust particles. Therefore, direct detection of freshly produced radionuclides ‘live’ on Earth, i.e. before decaying, would provide insight into recent and nearby nucleosynthetic activities. A pioneering work at TU Munich of an ocean crust-sample showed an enhanced $^{60}$Fe signal of extraterrestrial origin — does it originate from a close-by supernova about 2-3 Myr ago?

Exomoons as Tracers of Exoplanet Formation and Evolution

Dr. René Heller

(Max-Planck-Institut für Sonnensystemforschung Göttingen)

Freitag/Friday, 2016-04-29 15:00 c.t., Seminarraum EW 431

Eugene-Paul-Wigner Gebäude, Hardenbergstr. 36, 10623 Berlin

Zusammenfassung/Abstract:

While about 4,000 planets and planet candidates have been found outside the solar system, no moon around an exoplanet (or "exomoon") has been found so far. In the solar system, moons serve as records of planet formation, e.g. of the conditions in the accretion disk around the early Jupiter. Exomoon observations could thus provide extremely valuable insights into exoplanet formation and evolution, which are not accessible via exoplanet observations alone. New simulations indicate that moons as massive as planet Mars can form around super-Jovian giant exoplanets, and recent advances in exomoon detection methods suggest that these large moons are observable with current (Kepler) and near-future (CHEOPS, PLATO, E-ELT) technology. Exomoons in the stellar habitable zones could thus be abundant extrasolar habitats.

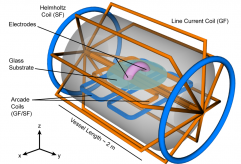

Solar eruptions, numerical simulation and laboratory experiments

Prof. Dr. Jörg Büchner

(Max-Planck-Institut für Sonnensystemforschung, Göttingen)

Freitag/Friday, 2015-12-18, 14 c.t., EW-561

Eugene-Paul-Wigner Gebäude, Hardenbergstr. 36, 10623 Berlin

Zusammenfassung/Abstract:The Sun releases its thermonuclear energy not only in form of the well know and a seemingly constant flow of white light but also by a highly variable stream of non-visible electromagnetic radiation, by plasma flows and energetic particles. Altogether these energy flows form the external environmental conditions for the planet Earth now called the "Space Weather". The Space Weather conditions are highly variable - even more than the atmospheric weather conditions. The reason is that the sources of the Space Weather are eruptive energy releases from the Sun with the most prominent Solar Flares and called Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs). The increasing social relevance of the Space Weather conditions has recently led to intensive efforts to understand of the reason of solar eruptions. We present the main existing models of solar eruptions as they actually are under development and demonstrate their verification by means of numerical simulations directly comparable with solar observations. We further compare these findings with the results of current laboratory eruption experiments carried out at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (MRX).

From darkness to light – the emergence of star clusters from molecular clouds

Dr. James Dale

(Universitäts-Sternwarte München, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität)

Dienstag/Tuesday, 2015-11-24 14:00 c.t., Raum EW-114

Eugene-Paul-Wigner Gebäude, Hardenbergstr. 36, 10623 Berlin

Zusammenfassung/Abstract:

The most important stage of a star cluster’s life is that in which it emerges from the molecular cloud in which it formed, and becomes optically visible. Over a short timescale, residual gas is expelled from the cluster, the remains of the cloud are dispersed, star formation is terminated, and the embedded stellar population, previously visible only in the infrared, becomes optically bright. I will present numerical simulations of this complex process, compare them with the latest observational results and discuss the implications of the current state of this field for the global star formation process.

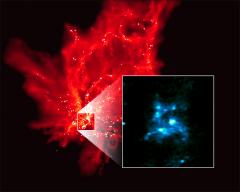

Modelling the stellar winds from hot and cool stars

- NGC 7635 (The Bubble Nebula) - A strong stellar wind and intense radiation from a star has blasted out the structure of glowing gas against denser material in a surrounding molecular cloud.

- © Bernard Michaud

Dr. Jonathan Mackey

(Argelander-Institut für Astronomie, Universität Bonn)

Dienstag/Tuesday, 2014-12-09 14:00 c.t., EW 229

Eugene-Paul-Wigner Gebäude, Hardenbergstr. 36, 10623 Berlin

Zusammenfassung/Abstract:

Mass loss from massive stars is very important for determining their evolution and death, but their wind properties can be difficult to measure and are often very uncertain.

Main sequence massive stars have fast and highly ionized winds, driving bubbles in their surroundings that have proven surprisingly difficult to detect. We have run simulations showing that wind bubbles are typically very asymmetric and do not fill their HII regions.